Thermal comfort in Moroccan housing is often treated as a secondary concern. Something addressed only through air conditioning, heavy curtains, or personal adaptation rather than intentional design. As a result, many dwellings experience pronounced thermal discomfort; interiors that overheat by midday in summer, grow uncomfortably cold in winter, and depend increasingly on mechanical systems to remain habitable. In this context, comfort becomes reactive rather than planned.

1. How buildings achieve thermal comfort

Thermal comfort is the result of how a building manages the interaction between its envelope and the surrounding climate. Central to this relationship is the building envelope, whose design, materials, and performance largely determine how interior spaces respond to external climatic conditions.

Insulation is a primary tool in regulating heat exchange. When effectively integrated into both opaque elements and glazed surfaces, it reduces unwanted heat gain during warmer seasons while limiting heat loss in colder periods. This controlled thermal barrier allows indoor temperatures to remain more stable.

Thermal inertia further moderates indoor conditions by influencing how quickly a building reacts to temperature changes. Governed by material choice and structural systems, thermal inertia describes a building’s capacity to absorb, store, and gradually release heat.

Finally, air ventilation plays a crucial role in completing the thermal strategy. By managing the exchange and circulation of air with the exterior, ventilation helps dissipate excess heat, control humidity, and maintain fresh indoor air.

2. Understanding thermal discomfort in housing

During winter days, if a house is poorly insulated , it loses heat faster than it can gain it. At night, the building envelope—walls, roof, windows, and floors—releases the heat stored during the day. If the structure has low thermal inertia, it cannot retain warmth for long, causing interior temperatures to drop rapidly. The outdoor environment may feel warmer due to sun exposure and movement, while the interior remains shaded, enclosed, and thermally disconnected from solar gains.

In summer, the situation often reverses. Buildings exposed to intense solar radiation absorb heat through roofs, walls, and especially poorly shaded glazing. When insulation and solar control are insufficient, this heat penetrates indoors. High thermal inertia materials can store this heat during the day and release it slowly into interior spaces, causing indoor temperatures to remain high well into the evening, even after outdoor temperatures have dropped. Limited natural ventilation exacerbates the problem. Without effective cross-ventilation , accumulated heat cannot be purged, and indoor spaces may remain warmer than the outdoor air. Urban density, surrounding spaces, and dark exterior finishes can further intensify heat absorption, reinforcing overheating.

Architecturally, achieving comfort depends not on isolating the building from its environment, but on designing the envelope to respond intelligently to seasonal changes.

3. How thermal performance is regulated in Morocco

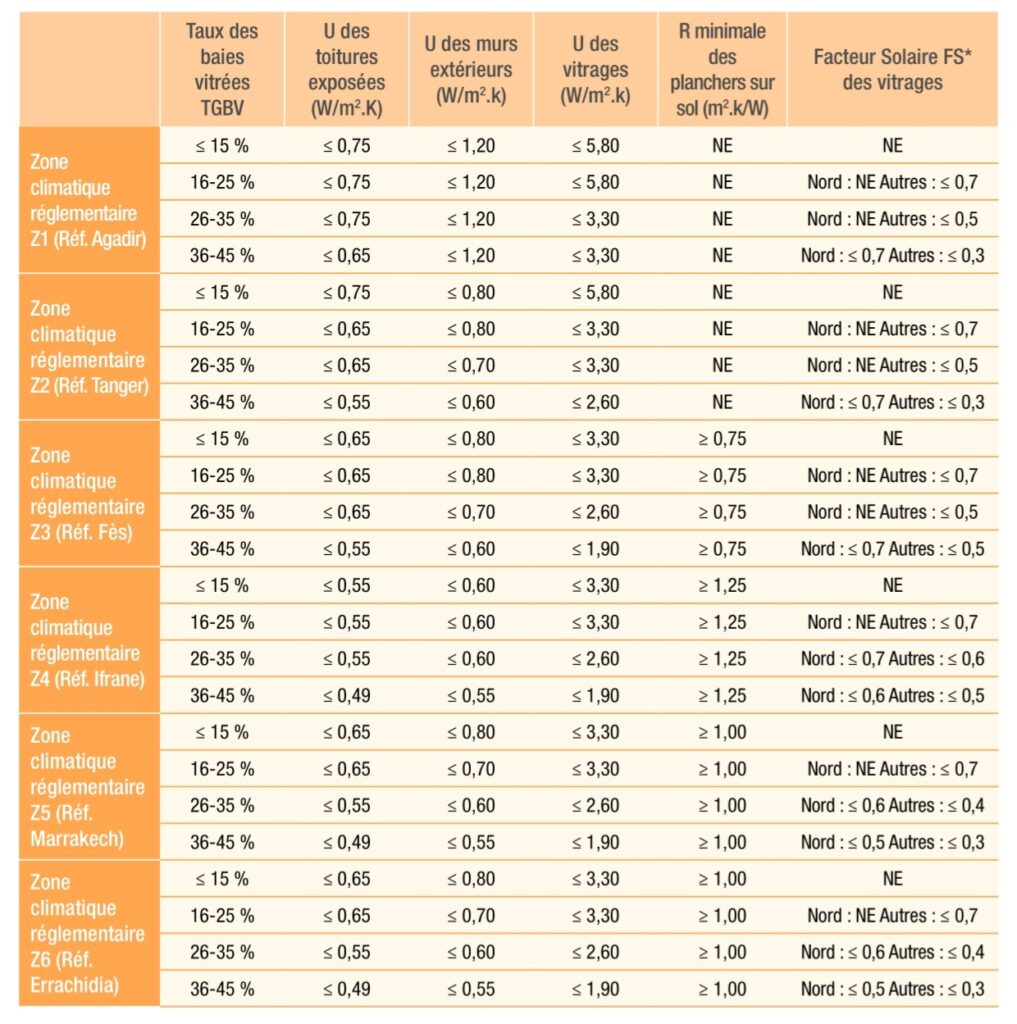

The Règlement Thermique de Construction au Maroc (RTCM) sets limits for the thermal performance of residential buildings. It organizes requirements by six climatic zones (Z1–Z6) and by the percentage of glazed openings (TGBV).

The regulation specifies:

. The maximum allowable U-values for roofs, exterior walls, and glazing.

. A minimum required thermal resistance (R) for floors in certain zones.

. Limits on the solar factor (FS) of glazing, which vary by orientation and glazing ratio.

Overall, the requirements become more demanding as climatic conditions intensify and glazing proportions increase, guiding envelope design to better control heat gains and losses.

4. Why thermal regulations fail to translate into practice

Despite the RTCM’s clear guidance, its impact in practice is limited. Several factors contribute to this gap:

1. Regulation without strong enforcement

Although the RTCM is legally in force, its application is rarely controlled. In many projects, compliance is treated as optional rather than mandatory. Building permits are often granted without a rigorous verification of thermal performance studies, and on-site inspections rarely focus on envelope performance. Without consistent enforcement mechanisms or penalties, the regulation remains largely declarative.

2. A design culture still driven by cost and speed

Much of Moroccan housing production—particularly in the middle- and low-income sectors—is driven by short-term cost minimization. Thermal performance is often perceived as an added expense rather than a long-term investment. As a result, insulation, solar control, and material performance are frequently reduced or omitted during construction, even when they appear in the design documents.

3. Weak integration into architectural education and practice

Thermal comfort and building physics are often underemphasized in architectural training, or treated theoretically rather than as design drivers. As a result, many buildings are conceived primarily through formal, regulatory, or economic constraints, with thermal performance addressed late—or not at all—rather than embedded from the earliest design stages.

4. Comfort still associated with mechanical solutions

There remains a widespread belief that thermal comfort can be “fixed” later through air conditioning or heaters. This mindset reduces the perceived importance of envelope performance and passive design strategies, despite their long-term economic and environmental benefits. Comfort becomes reactive rather than architectural.

5. Lack of public awareness and user demand

Finally, end users are often unaware of the RTCM and its benefits. Without demand from clients for thermally efficient buildings, developers have little incentive to go beyond minimum visible requirements. Energy performance remains largely invisible at the point of sale or rental.

Too often, comfort is treated as something added to buildings rather than formed by them. Re-centering thermal performance as an architectural concern allows housing to respond more naturally and intelligently to its climate.

Very informative!!

Well structured and clear. A delight to read as always!

Keep up the good work.

Thank you for your encouragement!

J’ai lu ce sujet avec grand intérêt car je m’intéresse au logement dans les zones rurales du Maroc. J’ai constaté que les habitants, forts de leur expérience de plusieurs générations, ont toujours privilégié l’isolation thermique de leurs maisons, que ce soit par le choix des techniques de construction (épaisseur des murs, forme du toit) ou par l’utilisation de matériaux locaux. Cela garantit une température intérieure confortable.

En ville, la situation évolue progressivement. Les nouveaux bâtiments intègrent de plus en plus les aspects thermiques pour deux raisons principales : d’une part, l’évolution de la société, notamment chez les jeunes familles et la nouvelle génération d’architectes, et d’autre part, le phénomène du changement climatique. Tous ces facteurs ont rendu nécessaire l’intégration des considérations thermiques dans la conception des bâtiments.

Cet article est bien conçu et pourrait servir de base à une étude permettant d’établir un diagnostic précis des techniques de construction actuelles et de proposer des pistes pour la construction de logements de qualité à un coût raisonnable. Je vous encourage à poursuivre vos recherches et vos écrits sur ces sujets importants, essayer d’animer d’avantage tes articles avec des illustrations…

Bon courage

Thank you for your feedback. I’ll work on integrating illustrations, photos and/or diagrams in the upcoming articles.